Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

| Adventures of Huckleberry Finn | |

|---|---|

1st edition book cover |

|

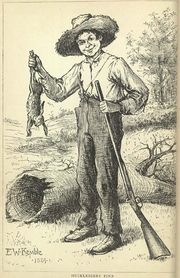

| Author | Mark Twain |

| Illustrator | E. W. Kemble |

| Cover artist | TAYLOR |

| Country | United Kingdom / United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | 1 |

| Genre(s) | Satirical novel |

| Publisher | Chatto & Windus / Charles L. Webster And Company. |

| Publication date |

1884 UK & Canada |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 366 |

| ISBN | NAA |

| OCLC Number | 29489461 |

| Preceded by | Life on the Mississippi |

| Followed by | A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court |

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (although Mark Twain was adamant that the word "The" was not in the title, it is often published and referred to as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or shortened to Huckleberry Finn or simply Huck Finn) is a novel by Mark Twain, first published in England in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885. Commonly recognized as one of the Great American Novels, the work is among the first in major American literature to be written in the vernacular, characterized by local color regionalism. It is told in the first person by Huckleberry "Huck" Finn, a friend of Tom Sawyer and narrator of two other Twain novels (Tom Sawyer Abroad and Tom Sawyer, Detective).

The book is noted for its colorful description of people and places along the Mississippi River. Satirizing a Southern antebellum society that was already out of date by the time the work was published, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is an often scathing look at entrenched attitudes, particularly racism.

The work has been popular with readers since its publication and is taken as a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. It has also been the continued object of study by serious literary critics. It was criticized upon release because of its coarse language and became even more controversial in the 20th century because of its perceived use of racial stereotypes and because of its frequent use of the racial slur "nigger".[2][3]

Contents |

Publication history

Twain initially conceived of the work as a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer that would follow Huck Finn through adulthood. Beginning with a few pages he had removed from the earlier novel, Twain began work on a manuscript he originally titled Huckleberry Finn's Autobiography. Twain worked on the manuscript off and on for the next several years, ultimately abandoning his original plan of following Huck's development into adulthood. He appeared to have lost interest in the manuscript while it was in progress, and set it aside for several years. After making a trip down the Mississippi, Twain returned to his work on the novel. Upon completion, the novel's title closely paralleled its predecessor's: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade).[4]

Unlike The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn does not have the definite article "the" as a part of its proper title. Essayist and critic Spencer Neve states that this absence represents the "never fulfilled anticipations" of Huck's adventures—while Tom's adventures were completed (at least at the time) by the end of his novel, Huck's narrative ends with his stated intention to head West.[5]

Mark Twain composed the story in pen on notepaper between 1876 and 1883. Paul Needham, who supervised the authentication of the manuscript for Sotheby's books and manuscripts department in New York in 1991, stated, "What you see is [Clemens'] attempt to move away from pure literary writing to dialect writing". For example, Twain revised the opening line of Huck Finn three times. He initially wrote, "You will not know about me," which he changed to, "You do not know about me," before settling on the final version, "You don't know about me, without you have read a book by the name of 'The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'; but that ain't no matter."[6] The revisions also show how Twain reworked his material to strengthen the characters of Huck and Jim, as well as his sensitivity to the then-current debate over literacy and voting.[7]

A later version was the first typewritten manuscript delivered to a printer.[7]

Huck Finn was eventually published on December 10, 1884, in Canada and England, and on February 18, 1885, in the United States. The American publication was delayed because someone defaced an illustration on one of the plates, creating an obscene joke. Thirty-thousand copies of the book had been printed before the obscenity was discovered. A new plate was made to correct the illustration and repair the existing copies.[8]

In 1885, the Buffalo Public Library's curator, James Fraser Gluck, approached Twain to donate the manuscript to the Library. Twain sent half of the pages, believing the other half to have been lost by the printer. In 1991, the missing half turned up in a steamer trunk owned by descendants of Gluck. The Library successfully proved possession and, in 1994, opened the Mark Twain Room in its Central Library to showcase the treasure.[9]

Plot summary

Life in St. Petersburg

The story begins in fictional St. Petersburg, Missouri, on the shores of the Mississippi River, sometime between 1835 (when the first steamboat sailed down the Mississippi[10]) and 1845. Two young boys, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, have each come into a considerable sum of money as a result of their earlier adventures (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer). Huck has been placed under the guardianship of the Widow Douglas, who, together with her sister, Miss Watson, are attempting to "sivilize" him. Huck appreciates their efforts, but finds civilized life confining. In the beginning of the story, Tom Sawyer appears briefly, helping Huck escape at night from the house, past Miss Watson's slave, Jim. They meet up with Tom Sawyer's self-proclaimed gang, who plot to carry out adventurous crimes. Life is changed by the sudden appearance of Huck's shiftless father "Pap," an abusive parent and drunkard. Although Huck is successful in preventing his Pap from acquiring his fortune, Pap forcibly gains custody of Huck and the two move to the backwoods where Huck is kept locked inside his father's cabin. Equally dissatisfied with life with his father, Huck escapes from the cabin, elaborately fakes his own death, and sets off down the Mississippi River.

The Floating House & Huck as a Girl

While living quite comfortably in the wilderness along the Mississippi, Huck happily encounters Miss Watson's slave Jim on an island called Jackson's Island, and Huck learns that he has also run away, after Miss Watson threatened to sell him downriver, where conditions for slaves were even harsher.

Jim is trying to make his way to Cairo, Illinois, to get to Ohio, a free state, to buy his family's freedom. At first, Huck is conflicted over whether to tell someone about Jim's running away, but they travel together, they talk in depth, and Huck begins to know more about Jim's past and his difficult life. As these talks continue, Huck begins to change his opinion about people, slavery, and life in general. This continues throughout the rest of the novel.

Huck and Jim take up in a cavern on a hill on Jackson's Island to wait out a storm. When they can, they scrounge around the river looking for food, wood, and other items. One night, they find a raft they will eventually use to travel down the Mississippi. Later, they find an entire house floating down the river and enter it to grab what they can. Entering one room, Jim finds a man lying dead on the floor, shot in the back while apparently trying to ransack the house. He refuses to let Huck see the man's face.

To find out the latest news in the area, Huck dresses as a girl and goes into town. He enters the house of a woman new to the area, thinking she won't recognize him. As they talk, she tells Huck there is a $300 reward for Jim, who is accused of killing Huck. She becomes suspicious of Huck's true sex and these suspicions are confirmed when she sees he cannot thread a needle. She cleverly tricks him into revealing he's a boy, but allows him to run off. He returns to the island, tells Jim of the manhunt, and the two load up the raft and leave the island.

The Grangerfords and the Shepherdsons

Huck and Jim's raft is swamped by a passing steamship, separating the two. Huck is given shelter by the Grangerfords, a prosperous local family. He becomes friends with Buck Grangerford, a boy about his age, and learns that the Grangerfords are engaged in a 30-year blood feud against another family, the Shepherdsons. The Grangerfords and Shepherdsons go to church. Both families bring guns to continue the feud, despite the church's preachings on brotherly love.

The vendetta comes to a head when Buck's sister, Sophia Grangerford, elopes with Harney Shepherdson. In the resulting conflict, all the Grangerford males from this branch of the family are shot and killed, although Grangerfords elsewhere survive to carry on the feud. Upon seeing Buck's corpse, Huck is too devastated to write about everything that happened. However, Huck does describe how he narrowly avoids his own death in the gunfight, later reuniting with Jim and the raft and together fleeing farther south on the Mississippi River.

The Duke and the King

Farther down the river, Jim and Huck rescue two cunning grifters, who join Huck and Jim on the raft. The younger of the two swindlers, a man of about thirty, introduces himself as a son of an English duke (the Duke of Bridgewater, which the King later mispronounces as "Bilgewater") and his father's rightful successor. The older one, about seventy, then trumps the duke's claim by alleging that he is actually the Lost Dauphin, the son of Louis XVI and rightful King of France.

The Duke and the King then join Jim and Huck on the raft, committing a series of confidence schemes on the way south. To allow for Jim's presence, they print fake bills for an escaped slave; and later they paint him up entirely in blue and call him the "Sick Arab." On one occasion they arrive in a town and rent the courthouse for a night for the purpose of printing bills to advertise a play which they call the 'Royal Nonesuch'. The play turns out to be only a couple of minutes of hysterical cavorting, not worth anywhere near the 50 cents the townsmen were charged to see it.

Meanwhile on the day of the play, a drunk called Boggs arrives in town and makes a nuisance of himself by going around threatening a southern gentleman by the name of Colonel Sherburn. Sherburn comes out and warns Boggs that he can continue threatening him up until exactly one o'clock. At one o'clock, Boggs has already ceased his power and two friends are trying to hurry him out of town; but Colonel Sherburn kills him anyway. Somebody in the crowd, whom Sherburn later identifies as Buck Harkness, cries out that Sherburn should be lynched. They all head up to Colonel Sherburn's gate, where they are met by Sherburn, carrying a loaded rifle. Without saying a word, he causes them to back down, and then the crowd slinks away after Sherburn laughs and tells them about the essential cowardice of "Southern justice." The only lynching that's going to be done here, says Sherburn, will be in the dark, by men wearing masks.

On the third night of "The Royal Nonesuch," the townspeople are ready; but the Duke and the King have already skipped town, and together with Huck and Jim, they continue down the river. Once they are far enough away, the two grifters test the next town, and decide to impersonate the brothers of Peter Wilkes, a recently deceased man of property. Using an absurd English accent, the King manages to convince nearly all the townspeople that he and the Duke are Wilkes' brothers recently arrived from England. However, one man in town is certain that they are a fraud. The Duke suggests they should cut and run. The King continues to liquidate Wilkes' estate, saying, "Hain't we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain't that a big enough majority in any town?"

Huck likes Wilkes' daughters, who treat him with kindness and courtesy, so he tries to thwart the grifters' plans by stealing back the inheritance money. However, when he is in danger of being discovered, he has to hide it in Wilkes' coffin, which is buried the next morning without Huck knowing whether the money has been found or not. The arrival of two new men who seem to be the real brothers throws everything into confusion when none of their signatures match the one on record. (The deaf-mute brother, who is said to do the correspondence, has his arm in a sling and cannot currently write.) The townspeople devise a test, which requires digging up the coffin to check. When the money is found in Wilkes's coffin, the Duke and the King are able to escape in the confusion. They manage to rejoin Huck and Jim on the raft to Huck's utter despair, since he had thought he had escaped them.

Jim's escape

After the four fugitives have drifted far enough from the town, the King takes advantage of Huck's temporary absence to sell his interest in the "escaped" slave Jim for forty dollars. Outraged by this betrayal, Huck rejects the advice of his "conscience," which continues to tell him that in helping Jim escape to freedom, he is stealing Miss Watson's property. Accepting that "All right, then, I'll go to hell!", Huck resolves to free Jim.

Jim's new temporary owners are Mr. and Mrs. Phelps, who turn out to be Tom Sawyer's aunt and uncle. Since Tom is expected for a visit, Huck is mistaken for Tom. He plays along, hoping to find Jim's location and free him. When Huck intercepts Tom on the road and tells him everything, Tom decides to join Huck's scheme, pretending to be his younger half-brother Sid. Jim has also told the household about the two grifters and the new plan for "The Royal Nonesuch," so this time the townspeople are ready for them. The Duke and King are captured by the townspeople, and are tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail.

Rather than simply sneaking Jim out of the shed where he is being held, Tom develops an elaborate plan to free him, involving secret messages, hidden tunnels, a rope ladder sent in Jim's food, and other elements from popular novels,[11] including a note to the Phelps warning them of a gang planning to steal their runaway slave. During the resulting pursuit, Tom is shot in the leg. Jim remains with him rather than completing his escape, risking recapture. Huck has long known Jim was "white on the inside." Although the doctor admires Jim's decency, he betrays him to a passing skiff, and Jim is captured while sleeping.

Conclusion

After Jim's recapture, events quickly resolve themselves. Tom's Aunt Polly arrives and reveals Huck's and Tom's true identities. Tom announces that Jim has been free for months: Miss Watson died two months earlier and freed Jim in her will, but Tom chose not to reveal Jim's freedom so he could come up with an elaborate plan to rescue Jim. Jim tells Huck that Huck's father has been dead for some time (he was the dead man they found in the house on Jackson's Island) and that Huck may return safely to St. Petersburg. In the final narrative, Huck declares that he is quite glad to be done writing his story, and despite Tom's family's plans to adopt and "sivilize" him, Huck intends to flee west to Indian Territory.

Major themes

Twain wrote a novel that embodies the search for freedom. He wrote during the post-Civil War period when there was an intense white reaction against blacks. According to some critics, Twain took aim squarely against racial prejudice, increasing segregation, lynchings, and the generally accepted belief that blacks were sub-human. He "made it clear that Jim was good, deeply loving, human, and anxious for freedom."[12] However, others have criticized the novel as racist, citing the use of the word "nigger" and Jim's Sambo-like character.[2][3]

Throughout the story, Huck is in moral conflict with the received values of the society in which he lives, and while he is unable to consciously refute those values even in his thoughts, he makes a moral choice based on his own valuation of Jim's friendship and human worth, a decision in direct opposition to the things he has been taught. Mark Twain in his lecture notes proposes that "a sound heart is a surer guide than an ill-trained conscience," and goes on to describe the novel as "...a book of mine where a sound heart and a deformed conscience come into collision and conscience suffers defeat."[13]

Reception

The publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn resulted in generally friendly reviews, but the novel was controversial from the outset.[14] Upon issue of the American edition in 1885 a number of libraries banned it from their stacks.[15] The early criticism focused on what was perceived as the book's crudeness. One incident was recounted in the newspaper, the Boston Transcript:

The Concord (Mass.) Public Library committee has decided to exclude Mark Twain's latest book from the library. One member of the committee says that, while he does not wish to call it immoral, he thinks it contains but little humor, and that of a very coarse type. He regards it as the veriest trash. The library and the other members of the committee entertain similar views, characterizing it as rough, coarse, and inelegant, dealing with a series of experiences not elevating, the whole book being more suited to the slums than to intelligent, respectable people.[15]

Twain later remarked to his editor, "Apparently, the Concord library has condemned Huck as 'trash and only suitable for the slums.' This will sell us another five thousand copies for sure!"

Many subsequent critics, Ernest Hemingway among them, have deprecated the final chapters, claiming the book "devolves into little more than minstrel-show satire and broad comedy" after Jim is detained.[16] Hemingway declared, "All modern American literature comes from" Huck Finn, and hailed it as "the best book we've had." He cautioned, however, "If you must read it you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is just cheating."[17] (The term "Nigger Jim" never appears in the novel but after appearing in Albert Bigelow Paine's 1912 Clemens biography, continued to be used by twentieth century critics, including Leslie Fiedler, Norman Mailer, and Russell Baker.) Pulitzer Prize winner Ron Powers states in his Twain biography (Mark Twain: A Life) that "Huckleberry Finn endures as a consensus masterpiece despite these final chapters," in which Tom Sawyer leads Huck through elaborate machinations to rescue Jim.[18]

Much modern scholarship of Huckleberry Finn has focused on its treatment of race. Many Twain scholars have argued that the book, by humanizing Jim and exposing the fallacies of the racist assumptions of slavery, is an attack on racism.[19] Others have argued that the book falls short on this score, especially in its depiction of Jim.[15] According to Professor Stephen Railton of the University of Virginia, Twain was unable to fully rise above the stereotypes of black people that white readers of his era expected and enjoyed, and therefore resorted to minstrel show-style comedy to provide humor at Jim's expense, and ended up confirming rather than challenging late-19th century racist stereotypes.[20]

Because of this controversy over whether Huckleberry Finn is racist or anti-racist, and because the word "nigger" is frequently used in the novel, many have questioned the appropriateness of teaching the book in the U.S. public school system. According to the American Library Association, Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most frequently challenged book in the United States during the 1990s.[21]

Adaptations

Film

- Huckleberry Finn (1920) Silent starring Lewis Sargent as Huck, Gordon Griffith as Tom Sawyer [22]

- Huckleberry Finn (1931) First talkie-talk film, with Junior Durkin as Huck, Jackie Coogan as Tom [23]

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1939 film starring Mickey Rooney

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1954 film starring Thomas Mitchell and John Carradine produced by CBS ([2])

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn a 1960 film directed by Michael Curtiz, starring Eddie Hodges and Archie Moore

- The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1968 animated television series for children

- Hopelessly Lost, a 1972 Soviet film

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1974 musical film

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1975 ABC movie of the week with Ron Howard as Huck Finn

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1976 Japanese anime with 26 episodes

- Huckleberry Finn and His Friends, a 1979 television series starring Ian Tracey

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn(1981)(TV) Kurt Ida as Huckleberry Finn

- Rascals and Robbers: The Secret Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn (1982) (TV) Anthony Michael Hall as Huck Finn

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1985 television movie which was filmed in Maysville, Kentucky.

- The Adventures of Con Sawyer and Hucklemary Finn, a 1985 ABC movie of the week with Drew Barrymore as Con Sawyer

- The Adventures of Huck Finn, a 1993 film starring Elijah Wood and Courtney B. Vance

- Huckleberry Finn Monogatari, a 1994 Japanese anime with 26 episodes

- Tomato Sawyer and Huckleberry Larry's Big River Rescue, a VeggieTales parody of Huckleberry Finn created by Big Idea Productions with Larry the Cucumber as the titular character. ( 2008)

- Tom and Huck, a 1995 Disney live action film

Stage

- Big River, a 1985 Broadway musical with lyrics and music by Roger Miller

- Downriver, a 1975 Off Broadway musical, music and lyrics by John Braden

Literature

- The Further Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1983), a novel which continues Huck's adventures after he "lights out for the Territory" at the end of Twain's novel, by Greg Matthews.

- Finn: A Novel (2007), a novel about Huck's father, Pap Finn, by Jon Clinch.

- My Jim (2005), a novel narrated largely by Sadie, Jim's enslaved wife, by Nancy Rawles.

Music

- Mississippi Suite (1926), by Ferde Grofe: the second movement is a lighthearted whimsical piece entitled "Huck Finn"

- Huckleberry Finn EP (2009), comprising five songs from Kurt Weill's unfinished musical, by Duke Special

References

- ↑ Facsimile of the 1st US edition.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lester, Julius. Morality and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Woodard, Fredrick and MacCann, Donnarae. Minstrel Shackles and Nineteenth Century "Liberality" in Huckleberry Finn.

- ↑ Twain, Mark (2001-10-01). "Introduction". The Annotated Huckleberry Finn. introduction and annotations by Michael Patrick Hearn. W. W. Norton & Company. xiv–xvii, xxix. ISBN 0-393-02039-8.

- ↑ Young, Philip (1966-12-01). Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration. Penn State Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-271-02092-X.

- ↑ Reif, Rita (1991-02-14). "First Half of 'Huck Finn,' in Twain's Hand, Is Found". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE6D9103FF937A25751C0A967958260. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baker, William (1996-06-01). "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (book reviews)". Antioch Review (Antioch University) 54 (3): 363–4.

- ↑ Blair, Walter (1960). Mark Twain & Huck Finn. University of California Press.

- ↑ Reif, Rita. Antiques: How Huck Finn was rescued. New York Times, March 17, 1991 http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE7D81E3DF934A25750C0A967958260

- ↑ http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/PAO/history/MISSRNAV/steamboat.asp

- ↑ Victor A. Doyno (1991). Writing Huck Finn: Mark Twain's creative process. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 191. ISBN tk. [1]

- ↑ Leonard, James S.; Thomas A. Tenney and Thadious M. Davis (December 1992). Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn. Duke University Press. pp. 224. ISBN 9780822311744. http://books.google.com/?id=fdrBtpSSCisC&pg=RA1-PA116&lpg=RA1-PA116&dq=hemingway+%22huckleberry+finn%22+%22green+hills%22.

- ↑ Mark Twain: Critical Assessments, Stuart Hutchinson, Ed, Routledge 1993, p. 193

- ↑ Mailer, Norman (1984-12-09). "Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/09/books/mailer-huck.html. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Leonard, James S.; Thomas A. Tenney and Thadious M. Davis (December 1992). Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn. Duke University Press. pp. 2. ISBN 9780822311744. http://books.google.com/?id=fdrBtpSSCisC&pg=RA1-PA116&lpg=RA1-PA116&dq=hemingway+%22huckleberry+finn%22+%22green+hills%22.

- ↑ Nick, Gillespie (February 2006). "Mark Twain vs. Tom Sawyer: The bold deconstruction of a national icon". http://www.reason.com/news/show/36203.html. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest (1935). Green Hills of Africa. New York: Scribners. pp. 22.

- ↑ Powers, Ron (2005-09-13). Mark Twain: A Life. Free Press. pp. 476–7.

- ↑ For example, Shelley Fisher Fishin, Lighting out for the Territory: Reflections on Mark Twain and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Stephen Railton, "Jim and Mark Twain: What Do Dey Stan' For?" Virginia Quarterly Review 63 (1987).

- ↑ ALA | 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990-1999

- ↑ IMDB, Huckleberry Finn (1920)

- ↑ IMDB, Huckleberry Finn (1931)

External links

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Digitized copy of the first American edition from Internet Archive (1885).

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, 125th Anniversary Edition. University of California Press, 2010.

- "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". Publicliterature.org. http://publicliterature.org/books/huckleberry_finn/xaa.php. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". SparkNotes. http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/huckfinn/. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Study Guide and Lesson Plan". GradeSaver. http://www.gradesaver.com/classicnotes/titles/huckfinn/. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- "Huckleberry Finn". CliffsNotes. http://www.cliffsnotes.com/WileyCDA/LitNote/Huckleberry-Finn.id-20.html. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "Huck Finn in Context:A Teaching Guide". PBS.org. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/cultureshock/teachers/huck/index.html. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "Special Collections: Mark Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)". Libraries of Buffalo & Erie County. http://www.buffalolib.org/libraries/collections/index.asp?sec=twain. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- Smiley, Jane (January 1996). "Say It Ain’t So, Huck: Second thoughts on Mark Twain’s “masterpiece,”" (PDF). Harper’s Magazine 292 (1748): 61-. http://www.fhs.fuhsd.org/~dclarke/AM_LIT_H/READINGS/UNIT_2/finn_smiley_abbr.pdf.

- Both Chinese and English ebook online Easy Free in HTML format.

- Images of First English Edition (1884)

- Images of First U.S. Edition (1885)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a Gutenberg ebook

- Unit plan for teaching Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in Secondary Schools

|

||||||||||||||||||||